Health economics

I am deeply grateful to Dr. Hugo Turner and Asst Prof. Kiesha Prem for their invaluable support and guidance throughout the writing of this chapter.

Health economics focuses on how to allocate healthcare resources efficiently to maximize health outcomes with limited resources (Goeree & Diaby, 2013). Health economics is used to support decision-making in situations where we must choose between different options. For example, given the current budget, should we buy HPV vaccines or COVID-19 vaccines?

Health economics emphasizes opportunity costs, which are the benefits sacrificed when choosing one option over another. For example, the opportunity cost of purchasing COVID-19 vaccines is the potential benefits lost from not buying HPV vaccines.

Types of analyses

Partial economic evaluations: studies that either only examine cost or consequences, or examine both costs and consequences but for only one intervention (without a comparator). This analysis cannot guide decision-making (Turner et al., 2021).

Full economic evaluations: compare both the costs and consequences of the intervention to a comparator. There are 3 most popular types of full economic evaluations, the key difference lies in how they express the consequences (Turner et al., 2021):

| Type | Costs | Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Cost-effectiveness | $ | A single natural unit (life-years gained, cases averted, cases detected) |

| Cost-utility | $ | QALYs, DALYs |

| Cost-benefit | $ | $ |

- Cost-utility is sometimes considered as a special type of cost-effectiveness.

- There are 2 more types of full economic evaluations: cost-minimisation and cost-consequence, but they are less commonly used.

Models in health economics

Proportionate outcomes model

Also known as decision tree although exact definitions differ. Group flows divided into proportional outcomes over a single time period (Bishai et al., 2023).

All decision trees have 3 key components (Bishai et al., 2023):

- Decision nodes: where different comparators are compared.

- Chance nodes: where potential outcomes are weighted by their probabilities.

- Terminal nodes: endpoints of pathways, where costs and effectiveness calculated.

We have to specify a fixed time horizon represents the period over which probabilities and outcomes are considered (Kuntz et al., 2013). If a decision tree uses a 50-year time horizon, the probabilities of outcomes are based on what could occur within those 50 years.

- Decision nodes (or the comparators) are either “No vaccine” or “Vaccine” available.

- Chance nodes (or outcomes and their probabilities), are the nodes branch out from Decision nodes.

- Terminal nodes (or the endpoints for costs and effectiveness) are “No infection”, “Recovered”, and “Death”.

Markov model

A Markov model is a repeated decision tree (Heeg et al., 2008). The core elements of a Markov model are health states and transition (Bishai et al., 2023):

Health states represent different conditions such as being healthy, sick, disease stages, or vaccinated. States must be mutually exclusive (a person can’t be in two states at once) and exhaustive (cover all relevant conditions).

Transition is the probability (ranges between 0 and 1) of moving from one state to another.

Markov models are used for problems that involve risk over time, or when the timing of events is important (Kuntz et al., 2013). We can use a Markov model to represent the endpoints shown in the decision tree Figure 1.

| S | V | I | R | D | Check | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible (S) | 0.198 | 0.100 | 0.700 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 1.000 |

| Vaccinated (V) | 0.000 | 0.998 | 0.000045 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 1.000 |

| Infected (I) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.129 | 0.865 | 0.006 | 1.000 |

| Recovered (R) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.998 | 0.002 | 1.000 |

| Deaths (D) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

The key disadvantage of a Markov model is its memoryless property or Markov assumption, which assumes that transitions between health states depend only on the current state, not on the past history or duration spent in a state (Bishai et al., 2023).

Compartmental dynamic model

Static models (decision tree, Markov model) assumes that the force of infection is constant or changes only as a function of age and other individual characteristics. Dynamic model assumes that the force of infection can vary throughout the course of time and as a function of population interactions. Dynamic models are preferable for modeling the impact of a vaccine when considerations of herd immunity (Bishai et al., 2023).

We can adjust the Markov model Figure 2 to become a compartmental dynamic model by specifying that the force of infection varies over time.

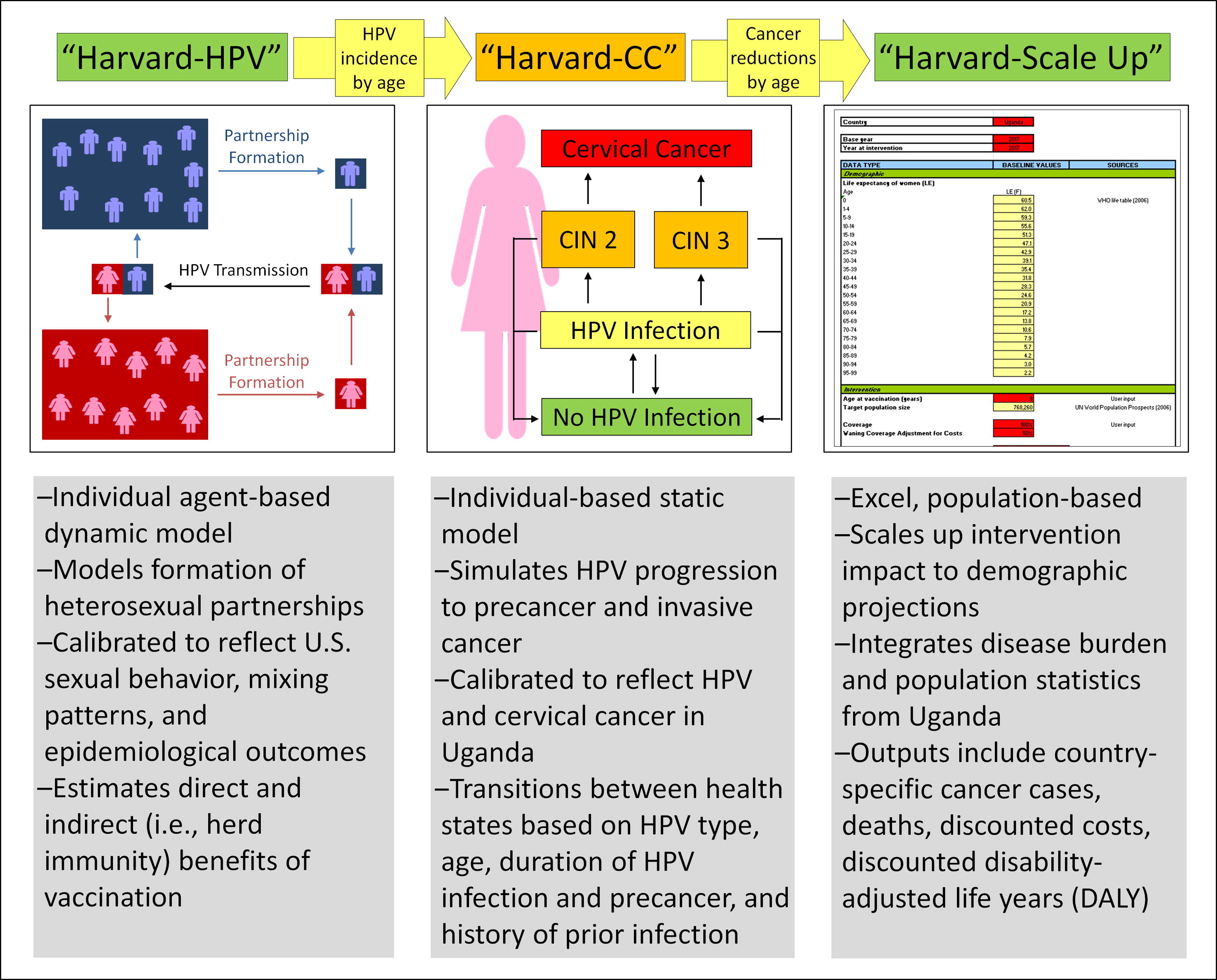

Individual-based model

Individual-based model, also called microsimulation model, keeps track of each individual’s behaviour (Kim & Goldie, 2008). This is done by repeatedly sampling from probability distributions a large number of times to understand the average and spread of potential results. The disadvantage is that they are time-consuming, as they require sometimes the simulation of millions of individuals to obtain stable estimates (Bishai et al., 2023).

Choice of model

The most difficult decision in model building is “How complex should the model be?” (Hilborn & Mangel, 1997). Most modellers agree on 2 basic rules for choosing a model:

- Let the data tell you (Hilborn & Mangel, 1997).

Simpler models need less data to estimate parameters but might overlook important system components. In contrast, complex models can capture more details but we may not have sufficient data to determine the parameters (Hilborn & Mangel, 1997).

- The use of the model (Hilborn & Mangel, 1997).

Simple models are useful if their assumptions are reasonable. For accurate predictions, a “wrong” but simpler model can do better than the “right” but complex model when parameters are estimated (Hilborn & Mangel, 1997). However, a complex model provides a better representation of uncertainty (Hilborn & Mangel, 1997).

Given the close connection between health economics and policy, guidelines are available for every step of the process. Be sure to read and follow these guidelines when conducting your analysis. Below is guidance on choosing between static and dynamic models.

Measuring consequences

Utility

Utility of health states are expressed on a scale from 0 to 1, where 0 represents the utility of being “dead” and 1 represents the utility of “perfect health” (Prieto & Sacristán, 2003).

QALY

The quality-adjusted life year (QALY) measure “years lived in perfect health”. One year in perfect health equals 1 QALY (1 Year \(\times\) 1 Utility = 1 QALY). A year lived in less than perfect health is worth less than 1 QALY (Prieto & Sacristán, 2003).

\[\text{QALY} = \sum_{i = 0}^{\text{lifetime}} \text{Year} \times \text{Utility}\]

For example, 0.5 years in perfect health equals 0.5 QALYs (0.5 years \(\times\) 1 Utility), the same as 1 year with a utility of 0.5 (1 year \(\times\) 0.5 Utility) (Prieto & Sacristán, 2003). The area under the curve equates to the total QALY value (Whitehead & Ali, 2010).

Measuring costs

Perspectives

| Costs | Health care payer | Health care providers | Healthcare sector | Health system | Patient/ household | Societal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct medical costs paid by health care payer/providers | Y (only payer) | Y (both payer + provider) | Y | Y | Y | |

| Direct medical costs paid by patients (i.e., out-of-pocket) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Direct non-medical costs incurred by patients (travel, food, and accommodation) | Y | Y | ||||

| Productivity costs (e.g., monetized productivity | Varies | Varies | ||||

| Non-health sector costs (e.g., spillover impacts affecting other sectors such as education, criminal justice, etc.) | Y* | Y* | ||||

| Total | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

Discounting vs inflation

Discounting is needed if a longer time horizon than 1-2 years is being considered. For most health economic evaluations, guidelines recommend a discount rate of 3% (high-income countries) to 5% (low- and middle-income countries) (Bishai et al., 2023).

Discounting is adjusting future costs and outcomes of health-care interventions to “present value” (Severens & Milne, 2004). Discounting is based on the concept of “positive time preference”, meaning that people prefers to benefit sooner rather than later (Severens & Milne, 2004).

\[\text{Present value} = \frac{\text{Future value}}{(1 + \text{annual discount rate})^\text{n years}}\]

Imagine you can choose between getting (A) $1000 today or (B) $1000 in 5 years. Most people prefer option A because having $1000 today allows you to use it immediately or invest it. The value of $1000 today is greater than $1000 in 5 years due to the opportunity to earn interest or invest it.

Now imagine you can choose between getting $500 today or $1000 in 10 years. To make a fair comparison, you need to adjust the future value to present value. Let’s say the discount rate is 5%. How much does $1000 in 10 years worth today?

\[\text{Present value} = \frac{1000}{(1 + 0.05)^{10}} \approx 613.91\]

So $1000 in 10 years is worth about $614 in today’s dollars.

Discounting should not be confused with adjusting for inflation. Both are needed. Discounting reflects the loss in value when there is a delay in obtaining an item of value (e.g., adjusting for future value). The inflation adjustment reflects the change in purchasing power of currency (e.g., adjusting past costs to current values).

Discounting: This is about the idea that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar in the future. It reflects our preference for receiving benefits or money sooner rather than later. It’s used to adjust future costs or benefits to their present value.

Inflation: This is about how the general price level of goods and services increases over time. Inflation means that money loses its purchasing power, so what $1 buys today might cost more in the future.

Define methods of value analysis

Net monetary benefit (NMB) or benefit-cost ratio

Compares alternative interventions in terms of their net social cost, defined as the difference of the social cost and social benefit, expressed in monetary value.

\[\text{NMB} = \text{Benefit of intervention} - \text{Cost of intervention}\]

Sometime, this value assessment is done by calculating the benefit-cost ratio:

\[\text{Benefit-cost ratio} = \frac{\text{Benefit of intervention}}{\text{Cost of intervention}}\]

When benefit > cost, meaning that NMB > 0 or benefit-cost ratio > 1, the intervention is said to be cost beneficial, and to represent good value for money.

When two interventions are being compared, report the incremental NMB which shows how intervention 1 is better than intervention 2.

\[\text{Incremental NMB} = \text{NMB}_1 - \text{NMB}_2\]

Incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER)

The ICER is the single most important interpretation of a CEA (Bishai et al., 2023). Compares two or more alternative interventions in terms of their efficiency, by relating their cost and outcomes.

\[\text{ICER} = \frac{\Delta \text{Cost}}{\Delta \text{Effectiveness}} = \frac{\text{Cost}_1 - \text{Cost}_2}{\text{Effectiveness}_1 - \text{Effectiveness}_2}\]

- ICER < 0:

- \(\Delta \text{Cost} < 0\) and \(\Delta \text{Effectiveness} > 0\): Intervention 1 is cheaper and has greater effectiveness (good).

- \(\Delta \text{Cost} > 0\) and \(\Delta \text{Effectiveness} < 0\): Intervention 1 is more expensive and has less effectiveness (bad).

- ICER > 0: Intervention 1 is more expensive, but also has greater effectiveness. In this case, the ICER has to be compared to the decision maker’s willingness-to-pay threshold per unit of the outcome.